Parkinson’s disease patients strive through medication to quell their tremors, but voluntary motion and activity may be their best medicine.

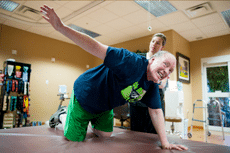

Dr. Jim Horrocks, an Omaha physician diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease about 10 years ago, sweated through his T-shirt as he tossed a basketball with physical therapist Christine Montes. He stretched and reached on a mat, and he strode with the help of a stabilizing harness in the gym of Life Care Center of Elkhorn.

The facility has invested thousands of dollars in Parkinson’s programs over the past couple of years.

Exercise programs for Parkinson’s disease patients have popped up nationwide in nursing homes, rehab centers and hospitals, which are investing time and money in staff certification, classes and equipment. The attention placed on the neurological disease makes sense because it typically afflicts older people, and waves of baby boomers are becoming senior citizens.

From Columbus Community Hospital to the Council Bluffs YMCA and well beyond, physical and speech therapists and patients themselves now push exercise in hopes of slowing the progression of a harsh disease that has no cure.

Horrocks, 64, walks with a pronounced lean and sometimes uses ski poles for stability. He has ceased driving and now practices medicine only part-time, mainly as a consultant on workplace injury cases. He has thrown his energy into exercise.

“The only thing worse than doing it is not doing it,” he said in the Life Care gym, where he gets outpatient exercise therapy. He looked over at his daughter, Meganne Storm, who had driven him that morning to the Elkhorn facility. “Are we having fun yet?” he asked her.

Recognition of the importance of exercise for patients like Horrocks has come relatively recently.

Dr. John Bertoni said physicians in the past relied heavily on drugs for Parkinson’s patients. In truth, he said, a combination of medicine and exercise can be beneficial, depending on the patient.

“The focus has been too much, unfortunately, on medications,” said Bertoni, director of the Parkinson’s disease clinic at Nebraska Medicine. Physicians have better information today and view exercise as legitimate therapy for Parkinson’s patients, he said.

Lauren Kesteloot, a physical therapist with Nebraska Medicine-Bellevue, said that 20 years ago, Parkinson’s disease patients received little encouragement to exercise. And that was understandable, because many have balance and mobility problems.

While therapists must monitor Parkinson’s patients in exercise — some patients exercise while sitting, some work out one-on-one with a trainer, some are harnessed in so they can’t fall — the attitude toward exercise has changed.

“We understand that exercise is medicine,” said Michell Ruskamp, assistant director of rehabilitation services at Columbus Community Hospital.

Close to 25 years ago, a program called Lee Silverman Voice Training, or LSVT Loud, was created to help Parkinson’s patients speak more loudly and clearly. Many speak softly and walk with short, shuffling steps. Becky Farley broadened the concept into a full exercise program called LSVT Big about 10 years ago.

Farley, who has a Ph.D. in neuroscience, created a new program five years ago. It addresses flexibility, strength, posture, trunk rotation and other movements through dancing, boxing, aerobics, walking and many other activities. Her program, based in Tucson, Arizona, is called Parkinson Wellness Recovery, or PWR.

Other exercise programs have come along, including Delay the Disease, which was created eight years ago in Ohio and is used by three local YMCAs.

Scholarly studies and reports have confirmed the importance of exercise. A 2011 report in the journal Neurology said that “vigorous exercise and physical fitness should be highly encouraged” in those with Parkinson’s. The article also said that exercise consistently improves mental abilities.

Another report, published two years ago in Lancet Neurology, said “exercise should be considered an essential treatment for PD, particularly in individuals with mild to moderate disease.”

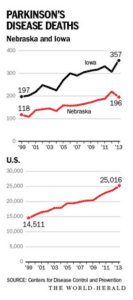

Parkinson’s disease is a growing challenge in Nebraska, Iowa and many other states.

A report published five years ago out of Washington University in St. Louis said that the Midwest and northeastern United States have the highest prevalence of Parkinson’s disease.

The Michael J. Fox Foundation, created by the actor who has become a spokesman for those with the disease, estimates that at least 1 million Americans have it. The affliction is caused by a lack of dopamine, a chemical that transmits signals in the brain that allow for coordination of movement.

Scientists believe that a combination of environmental factors and genetics lead to the disease. It can strike people much younger, but those older than 60 are at highest risk. David Drozd of the University of Nebraska at Omaha Center for Public Affairs Research estimated that the number of Nebraskans and Iowans over 60 increased by 25 percent and 20 percent respectively from 2000 to 2013.

CDC data, based on death certificates, indicates deaths with Parkinson’s disease as the underlying cause increased 60 percent nationwide from 2000 to 2013. The disease can cause poor posture, difficulty walking, rigidness, cognitive impairment and other problems. Parkinson’s typically doesn’t kill patients, but it can lead to falls that break hips, leading to pneumonia and infection, and thus it may be an underlying cause of death.

Facilities and organizations have responded to the explosion in Parkinson’s cases. Farley said that because there are so many Parkinson’s patients, and because information about the value of exercise is flowing, assisted-living centers and other institutions are signing on.

“People are hearing about exercise and that people can do more than they’re doing,” Farley said.

When Life Care Centers of America’s corporate leadership encouraged the Elkhorn staff to find an area of specialty a few years ago, the staffers chose Parkinson’s disease because of its prevalence in Nebraska.

Life Care Center of Elkhorn has put in an overhead track, or groove, to which harnesses can be hooked so patients won’t fall as they use a treadmill or walk about.

Close to 10 Life Care of Elkhorn staffers are certified in one or more Parkinson’s therapy strategies, such as Loud, Big, PWR and team training. Cheri Prince, director of rehabilitation services at Life Care of Elkhorn, said the center has spent close to $25,000 on training and certification over the past few years and about $50,000 on the track-and-harness system to keep exercising patients upright.

Horrocks played football at Nebraska Wesleyan University, then ran marathons and competed in triathlons. He refers to his sports background frequently as an element that motivates him.

He hears in his mind the voice of a high school football coach he encountered growing up in northeast Nebraska: “C’mon, c’mon!” the coach used to scream. “One more time!”

As Horrocks perspired his way through his workout, Lois Roberts sat in her motorized wheelchair in a room next to the gym.

Occupational therapist Rachel Beber used a metronome to help Roberts, 81, time wide, circular movements with her arms while Roberts also recited the alphabet. The metronome exercise helps with strength, timing, motor control and coordination, and it also requires Roberts to do two things at once, which can be difficult for Parkinson’s patients.

When Roberts’ circular motions dwindled and her voice became soft, Rachel took her hands from behind and helped them form wider circles while loudly reciting the alphabet.

“I swear, my brain is slowing down,” said Roberts, whose late husband, Joseph, served as mayor of Valley.

At a recent indoor picnic for the facility’s outpatients and residents with Parkinson’s disease, the staff showed a video of Davis Phinney, a former professional and Olympic bicyclist who has Parkinson’s.

Phinney, 55, said in a phone interview from Colorado that Parkinson’s patients shouldn’t spend their lives longing for a cure. They need to relish small victories and pleasures, he said, such as a cup of coffee, a walk, a hug, the feeling of the sun on the skin.

“To my mind, waiting in that way (for a cure) was relinquishing a certain amount of control,” he said. “And waiting was too passive a response.” Phinney advocates movement, group activities, good nutrition and not giving in.

“It’s really just finding one or more — hopefully more — activities that you can sustain, and that can sustain you,” he said.

Horrocks has taken pride in perseverance. When he played college football, he got punched while at the bottom of a pile, lost his front teeth and stayed in the game. While training for a triathlon many years ago, a pickup drilled him from behind and his shoulders and lower back were severely injured. His daughter said he’s always had the attitude that setbacks are challenges.

Horrocks recently went for a walk in his neighborhood. He reached an incline and began to worry that he might fall as he walked down the hill. He called his wife, Patty Sullivan, and asked her to pick him up in the car.

It’s disappointing, he said. There are times when he wonders, what’s the use? It’s a bumpy ride. But since attending the formal exercise program at Life Care over the past few weeks, he said, he notices that his coordination has improved somewhat and it’s much easier to get out of bed. He continues working at it.

He hears that football coach from his boyhood, imploring him to keep going.